Dear friends,

This is A Procrastination, an email newsletter from Hong Kong: City on Fire.

World-renowned China scholar Geremie Barmé calls Hong Kong the “Best China”. Well, we certainly saw the Best China on display yesterday.

Hong Kong Votes

It is unusual for local council elections to generate much excitement even in the city in which they are being held, let alone to make headlines across the globe.

Yet yesterday’s District Council elections in Hong Kong did just that, with the eyes of the world watching to see who would have the power to decide where to put an extra rubbish bin, remove a tree or build a park bench in the Hong Kong suburbs.

Of course, yesterday’s District Council elections were about much more than that, as I explained in last week’s Procrastination. They were, more than anything else, a referendum on the past six months of protests and an opportunity to obtain an objective measure of what the Hong Kong people are thinking.

For months the Hong Kong government and Pro-Beijing politicians had been banging on about Hong Kong’s “silent majority”. Yesterday, that silent majority finally spoke. They just didn’t say what the government was expecting them to say.

Key Data

You will have seen reports of the results in your news outlet of choice. Just to recap, here is the key data coming out of Sunday’s District Council election:

Highest-ever turnout for a Hong Kong election, with 2.9 million voters (out of 4.1 million total eligible voters) casting a vote, representing a turnout of 71%.

Pan-Democrat (i.e. anti-government/pro-protester) candidates won 385 seats; Pro-Beijing (“establishment”, pro-government) candidates won only 59 seats; 8 seats went to independents. (For comparison, in the 2015 District Council election the split was Pan-Dem 126 seats; Pro-Beijing 298 seats; independent 7 seats.)

Pan-Dems won control of 17 out of the 18 District Councils. Pan-Dems previously controlled none. On 2 of the 18 councils — Wong Tai Sin and Tai Po — Pan-Dems won every single seat. (For one remaining council, Outer Islands, Pan-Dems won a majority of the seats open to popular vote but Pro-Beijing parties retain control due to ex officio positions given to rural chiefs.)

Pan-Dems won around 57% of the popular vote; Pro-Beijing won around 41% of the popular vote.

Because they control a majority of District Council seats, Pan-Dems will appoint 117 District Council representatives to the 1,200-member Chief Executive Election Committee in 2022. (Unless the rules are changed before then?)

The results are unequivocal: a clear majority of Hong Kongers — despite the violence, vandalism and disruptions of recent months — support the protest movement and lay the blame for the ongoing chaos at the feet of Chief Executive Carrie Lam, her government and the Pro-Beijing politicians who support her.

The View from the Ground

With escalating violence in recent months, and the chaos of the past two weeks (summarised in my piece for New Statesman last week: The week Beijing let Hong Kong burn), the Pan-Dem candidates were not taking this election for granted. In the days leading up to election day, one Pan-Dem candidate told me:

“If this election had happened two months ago, we would have won in a landslide. Now? After the past few weeks? A lot of people are annoyed with us, or aren’t going to bother voting at all.”

Volunteers working for another candidate said:

“Support has been up and down. Last week [when roads were blocked] people were blaming us and yelling at us. It seems better this week. We are cautiously optimistic.”

But from the earliest hours of election morning, the day felt different. Queues were forming even before polling stations opened at 7:30am. As I headed out at around 9am there were queues stretching around the block at several polling stations.

As the government announced hourly turnout figures during the course of the day, it became clear that Hong Kongers were voting as they had never voted before. High turnout has traditionally favoured the Pan-Dems, and as the turnout figures soared, so did optimism on the Pan-Dem side.

The government had said they would station riot police at every polling booth “to ensure the safety of the voters”. This raised fears of a heavy-handed, intimidating police presence at the polling booths, but thankfully the police were sensibly very low-key; there was little visible police presence at the polling stations I visited.

Despite the spectre of possible violence looming on both sides, the day was peaceful and largely incident-free, the election conducted with the orderly efficiency for which Hong Kong is known.

Campaigning continued vigorously throughout the day, with candidates and their volunteers rallying support at the borders of the “no canvass zones” near the polling stations. What did campaigning look like? In densely-populated Hong Kong, it is very personal — the candidates wearing sashes like beauty pageant contestants — and happens on the streets. This video gives a sense of the scenes that played out at the busiest intersections and in housing estates throughout Hong Kong on election day:

After polls closed at 10:30pm, the polling stations became counting stations, open to any members of the public who wished to watch the count. It is a remarkable level of transparency — “democracy” happening before your very eyes — and an experience I found to be inspiring and really quite moving.

Counting underway in the Hong Kong District Council election on Sunday.

At the first count I attended, a crowd of around twenty observers watched as counters sorted ballot papers and put them into boxes labelled for Candidate Number 1 (the Pro-Beijing incumbent) and Candidate Number 2 (the Pan-Dem challenger). An intense hush hung over the room, the atmosphere solemn. Most of the observers seemed to be young — some were live-streaming the count to Facebook — and as the ballots for Candidate Number 2 piled up at a rapid rate, a thrill went through the crowd. Someone among the supporters uttered, sotto voce, the protest slogan “光復香港!” (“Restore Hong Kong!”) And another replied, a tremble in their voice, “時代革命!” (“Revolution of our times!”)

The scrutineer announced the initial count: the Pan-Dem candidate had around 3,000 votes to the Pro-Beijing candidate’s 2,000 votes, with only a small handful of questionable/disputed ballots to be considered. The Pan-Dem candidate was going to win. He pumped his fist, came out into the crowd to shake hands with some of this supporters and exchange a few hushed words while they waited for the final result to be officially declared.

I decided to leave and move on to the next counting station. As a middle-aged woman in a security guard uniform, her hair tied back in a bun, opened the door of the primary school to let me out, she asked, “Is it finished?”

“Not yet,” I said, “But Number 2 will win.”

“Which one was that?” she furrowed her brow, tense.

“The Pan-Dem,” I said.

She relaxed and grinned. “Thank you,” she said.

What next?

A common refrain you would hear talking to protesters on the streets in recent months is: “We have struggled so hard, we have paid such a high price, we can’t walk away with nothing.” Yesterday all of those efforts on the streets converted into a very tangible outcome, into real political power. It would seem to present an opportunity for the protesters to pause, regroup and consider next steps for their ambitious but messy movement. But looking ahead, it seems likely that protesters will be emboldened by the result to continue to push for their “5 Demands”.

The Pan-Dem politicians will feel obliged to back up the protesters with more concrete action from their side too. They know that many of them are in their positions only at the sufferance of the protesters: many of Hong Kong’s activists regard the establishment Democrats as being too soft and ineffectual. In the lead-up to election day, messages online implored young voters to get out and vote in spite of their dislike of the traditional Pan-Dem politicians, reminding them that they were really “voting out the Pro-Beijing parties”. Pan-Dems may be forced to take a more militant line if they want to appeal to their new constituents and continue to enjoy their support going into the LegCo elections next year, as they compete alongside younger, more radical parties. Indeed, the first order of business today was for the elected Pan-Dem candidates to rally at the site of the PolyU siege, where a small number of protesters remained holed-up inside a police cordon.

On the Pro-Beijing side, this result is likely further to increase tensions between the Pro-Beijing parties and Carrie Lam’s administration. They already (quite rightly) felt that Lam had thrown them under the bus with the extradition bill fiasco, and they (again, probably quite rightly) will blame her for this epic drubbing. But they might also want to re-examine their historical inclination uncritically to champion every single policy initiative coming out of the CE’s office regardless of its merits. If the Pro-Beijing parties began responsibly to fulfil their roles as members of Hong Kong’s third branch of government, rather than to act as megaphones and rubber-stamps for the administration, the legislature might finally be able to operate as the check-and-balance on the executive that it is designed to be.

As for Carrie Lam: this is the sort of electoral smashing that would presage the fall of governments and the resignation of leaders anywhere else. Of course those rules don’t apply here. Lam remains at Beijing’s pleasure, and Beijing is unlikely to want to do anything that suggests there is a connection between the ballot box and senior leadership.

Might this nevertheless prompt a cabinet reshuffle? Secretary for Security, John Lee, and Secretary for Justice, Teresa Cheng, have the magic combination of being unpopular and inept, and may be scalps to offer if any are needed.

The behaviour of the Hong Kong Police has been one of the key grievances of Hong Kongers, and Lam might see this as a signal for the need to re-assert civilian control over and impose accountability on the force. Again, this is probably also out of Lam’s hands, although it is interesting to see a number of Pro-Beijing figures are now supporting the idea of an independent inquiry, and that may be on the cards at some point in the future — but don’t worry, not until it would be too little, too late.

And, most critically, what about Beijing? What is their reaction likely to be?

Well-connected former long-term Beijing resident and senior editor at Foreign Policy, James Palmer, wrote on Twitter today that, based on information from multiple sources inside PRC state media, “Beijing genuinely thought they were going to win big in the elections today, to the point of having pre-written the stories.”

They were forced quickly to re-write those stories, and the official narrative now being trotted out in PRC state media is that the election result was due to “foreign interference”, in particular from the US, and “dirty tricks” on the part of the Pan-Dems.

Beijing knows — as well as everyone else — that none of this is true. But for Beijing this result is more than just an an intolerable loss of face. Beijing appears to have been genuinely surprised by this result — and Beijing does not like to be surprised by anything that happens within its borders. (Recall what happened after they were “surprised” by Falun Gong supporters rallying around Zhongnanhai in 1999.)

Make no mistake: this election result will not be seen by Beijing as a sign that they need to change tack in their approach to Hong Kong. It will not be the catalyst for some grand compromise. It will be seen as a sign that the Hong Kong people are making the wrong choice, and action needs to be taken to correct them. This is an emergency — one that, one way or another, Beijing will need to address before the more important Legislative Council elections in September 2020.

Yesterday brought us the fruits of Hong Kong’s Summer of Discontent. Time to brace ourselves for Winter?

In Closing

This has been A Procrastination. Thanks for reading.

Antony

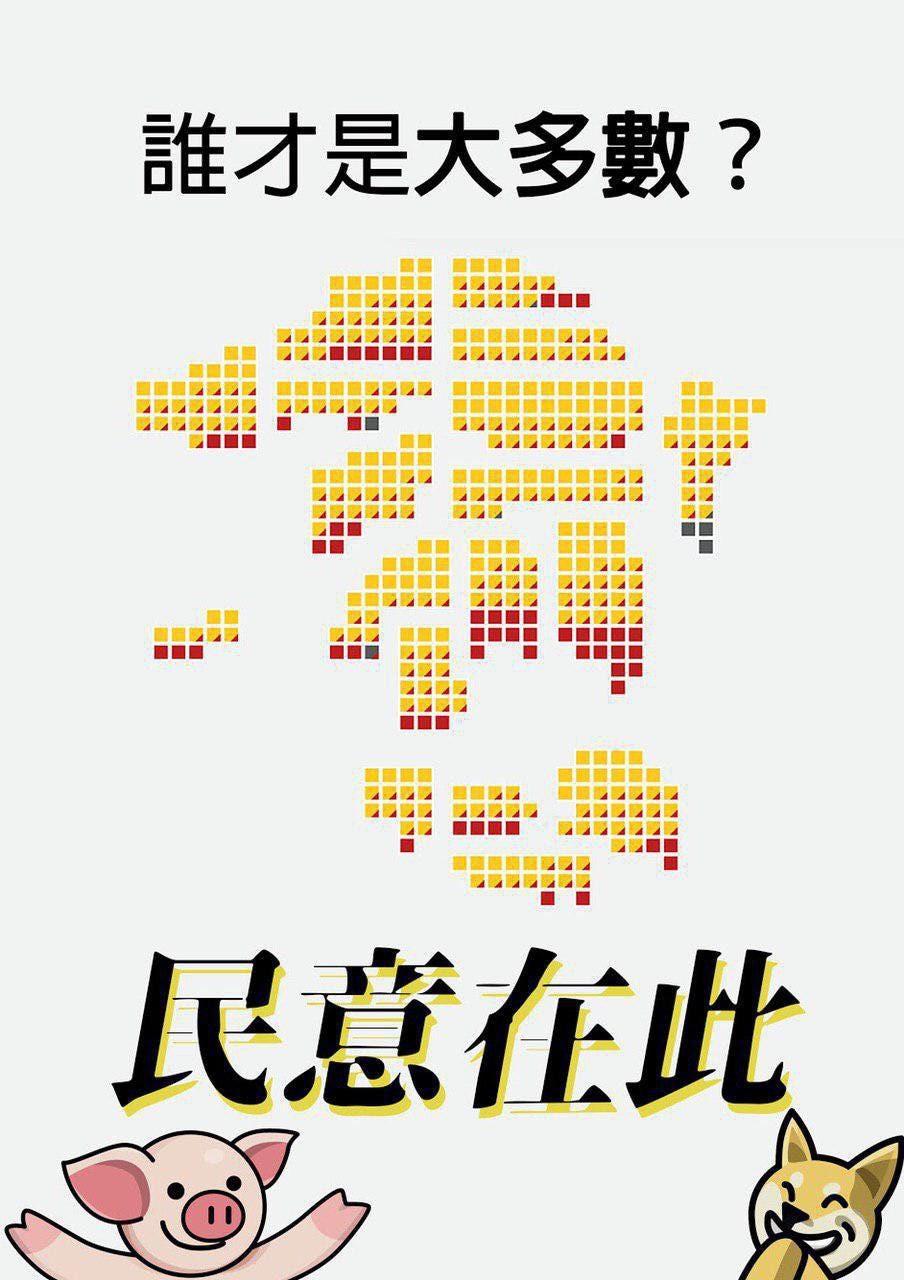

“Who is the majority? The popular will is here” Protester graphic, with the post-election District Council electoral map: yellow is Pan-Dem, red is Pro-Beijing, grey is independent. The corners indicate the colours seats were before they “flipped”. (Source: Protester channels via Telegram.)

Was this forward to you by a friend? Sign up for free here and receive A Procrastination direct to your inbox!